Quarantine Music, Andante But Never Agitato

From Singing All the Verses: Essays from a Mid-American

A few years ago, I was ambling through one of those antique stores composed of bookshelves, tables of different heights, glassed-in display cases with peculiar locks, and usually a section of wall with a display of prints, mounted paper ephemera, and a moose head mount. My husband and I do this browsing for relaxation, everywhere we go. We’ve spent many quiet hours perusing the detritus of lives unseen, objects now separated from their manna—that is, whatever power they once retained in the context of their bygone humans. Without their people, most of these objects seem a little reduced, a little dusty, a little lost. Look at this, we’ll say to each other. I’ve never seen one like this, one of us will say. Occasionally, we pick something up and bring it home.

A few years ago, I was ambling through one of those antique stores composed of bookshelves, tables of different heights, glassed-in display cases with peculiar locks, and usually a section of wall with a display of prints, mounted paper ephemera, and a moose head mount. My husband and I do this browsing for relaxation, everywhere we go. We’ve spent many quiet hours perusing the detritus of lives unseen, objects now separated from their manna—that is, whatever power they once retained in the context of their bygone humans. Without their people, most of these objects seem a little reduced, a little dusty, a little lost. Look at this, we’ll say to each other. I’ve never seen one like this, one of us will say. Occasionally, we pick something up and bring it home.

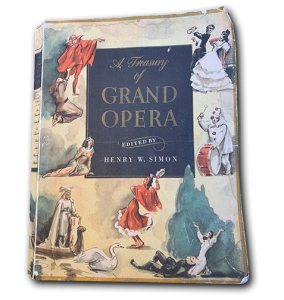

That is how I came by my present quarantine companion, A Treasury of Grand Opera, published in 1946 by Simon and Schuster. As soon as I saw it sitting on a table amid some undistinguished pottery and a bowl of key chains, I knew it was mine. Oversized, soft-covered, the book’s front and back are both adorned with simple watercolors of famous opera moments—Carmen shaking her tambourine, Aida reclining in a sultry pose, both characters with mouths open in song. That must be Mephistopheles in the red with the dramatic posture, sweeping his cape over his face. Only a little water-stained, in good shape really, and inside, the book contains four-hundred-and-four slightly tattered pages of production histories, vignettes, musical descriptions, and marvelous details. The principal characters of each opera are listed, the mise en scène described, the first performance date and location noted. And the chorus parts are also listed: for Carmen, I did not remember that the company is filled out with “dragoons, gypsies, smugglers, cigarette girls, officials and urchins.”

The core of the book, and its chief appeal to me, lies in page after page of piano scores for Don Giovanni, Lohengrin, La Traviata, Faust, Aida, Carmen, and Pagliacci. Suddenly, my largely empty apartment with a piano seems like an advantage. Be gone to my customary desultory fiddlings at the keyboard. Grand opera awaits. There is room for me amid the gypsies, urchins, and cigarette girls, and no one will know if I attempt the arias. I am all alone.

All this for five dollars. That is the same price the book sold for in 1946, but it is a steep discount when you consider the different value of the dollar. Five dollars in 1946 is the equivalent, I read, of $66 today. Bargain! This is the way you learn to think after a few decades of wandering the antique shops of the land.

And that is how I, in the time of coronavirus, have come to sit every day at my vintage upright piano, picking out the simplified arrangements of the great arias and filling in around them with a grand and complete orchestra in my head. Ridi, Pagliacco! I warble and give it a good slowdown, a molto ritard as the score indicates, as my avatar tenor throws his head up toward the hard-edged follow spot and lets his shoulders droop in the harlequin costume. “Laugh then, Pagliacco, for the love that is dying. Laugh through the pain that is destroying your heart!”, he sings. “Full-voiced to the breaking point,” says the score. “Expressively.” And, just before the final note, “sobbing.”

Good thing my husband is not at home when I play this. Good thing the apartment building has concrete walls.

I warble in English; my Italian is limited, if enthusiastic. I’ve picked my Italian up mostly from the subtitles of Metropolitan Opera broadcasts, which makes my vocabulary emphatic but not extensive. Coraggio! I can cry, meaning which means Courage! I can also exclaim in Italian “death”, “blood”, “kill”, and “vengeance”. In amorous vein I may say amore, that is, love both as a noun and a form of address, male and female. Cara, I say, or Caro! Dear,embrace me! Grand opera nearly always includes entreaty and penitence, and so I recognize “heavenly father” and “eternity” and “sin”. All of these words, plus contextual clues from staging, lights, and costumes — the mise en scène — enable me to understand most of the plots in grand opera. They do not make me a good conversationalist.

Being a person who is always interested in the backstory, I was rather hoping that Treasury editor Henry W. Simon would prove to be related to publisher Simon and Schuster, perhaps a disreputable cousin paid to stay offshore after some disgraceful episode, then falling in love with the Opera from a garret in Venice, just down the campo from Teatro La Fenice. Sad to say, not the case. But editor Mr. Simon tells a bit of his own story in the introduction to the collection. He writes:

“A Christmas present received over thirty years ago [that would make it before 1916, dear reader] is indirectly responsible for this book. It was a small badly bound collection of dreadfully simplified piano arrangements of the principal arias from several grand operas… Despite its palpable inadequacies, that little book inspired in my adolescent breast a love for grand opera that is today strong as ever. I played and read it through to pieces.”

I love these little glimpses into the backstory, why people are inspired to make something, and the travels these things subsequently make. My 1946 score is a direct descendant of that 1916 collection; I am working my way through it in 2020. I am quite considerably beyond adolescence, but I am as enthralled as young Henry likely was. Henry Simon died in 1970. I picked up the score in that dusty jumble shop some forty years after his death, and more than sixty after its publication. Where was it?

I have always loved sight-reading at the piano. I used to think this kind of brain exercise would stave off dementia, until a more musically literate and more worried-about-that friend told me it was memorizing, not sight-reading, that was useful. I still like sight-reading. It engages all of my attention, most of my senses, and some of my motor skills. I do not think about anything else while I’m playing through A Treasury of Grand Opera. I am not troubled by my mistakes or the awkward pauses when it’s time to turn the pages in a 404-page perfect-bound volume, actively trying to return to its closed state. A human page-turner, even if I had one, would defeat the purpose of free fumbling, and might disturb the mighty imaginary orchestra surrounding me at the piano.

Reading music is reading a foreign language, really, which I learned to understand in piano lessons that started in second grade. Thank you, Mrs. Salter. I am far from fluent now, but when I lay out a score on a tall table and page through it, I can feel my brain changing, knowing that I am seeing and hearing something that is blank to many people. It’s like a door that I know how to walk through. And on the other side is a breeze. When I set that score on the piano and my fingers on the keys, I feel it blowing.

I do not, however, seek humiliation. Therefore, I do not sight-read and play anything marked presto (at a rapid tempo) or even allegretto (fairly briskly) or, heaven forbid, agitato (to play quickly, with agitation and excitement). I am an andante player, which means a tempo that has something to do with walking, which I think of as related to rhythmic ease and steadiness and grace. It does not mean hurry. It does not mean “look out, here comes a complicated key change” or a series of sixteenth notes that blacken the staff or a sudden 9/8-time signature. Andante has something to do with heartbeat and with strength and communion, rather like the feeling of stepping into a choir and joining your voice to that of others. It gives permission to pause, looking ahead, and to simplify that left hand from rolling chords to a series of uncomplicated octaves. Andante allows space to hear the melody and to make it sing above the accompaniment.

And Andante is within my skill range, my range of right now. I turned away from serious piano study, and serious piano practice, when I first went to university and discovered that I really didn’t want to spend five hours a day in a practice room. It was, after all, 1968. People were marching across campus protesting and shouting and I was, for the first time, beginning to listen. I still have the sheet music for my freshman-year showpiece, the Brahms Rhapsody Opus 79 No. 2, and it is marked up with fingerings and notes and my dormitory room address. My hands still remember some of it. It is marked molto passionato, ma non troppo allegro. Very passionately, fast but not too fast. I have a dream that someday I’ll pick up the Brahms again, playing it passionately, but not too fast.

But for now my pleasure, and my distraction, is andante. Andante moderato. Or andante sostenuto, that is, sustained. And my vehicle is A Treasury of Grand Opera. In this time of social isolation, in a time of confinement and consideration, and of fear, I take my pleasures where I can, and join others in looking around ourselves for who we are.

These days, glancing behind reveals a landscape in which everything suddenly seems as antique as those dusty shops with outworn objects. A great crowd of people is in movement, and I can hear some of them, distantly and perhaps approaching, crying morte, death! And some of them are walking steadily and strongly, among them dragoons, gypsies, smugglers, cigarette girls, officials and urchins, and everyone I know and love. I can hear them singing, corragio, courage. Courage!