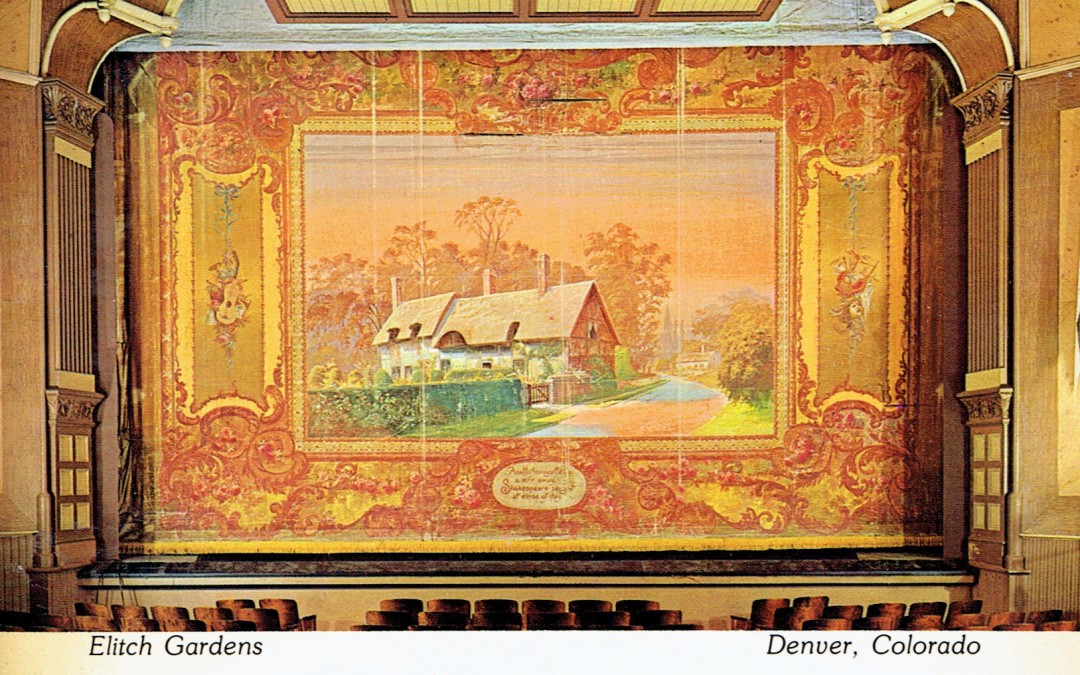

The Elitch Theatre, Denver’s grand old lady of summer stock theatres, where I was fortunate to work as stage manager a few decades ago, required a few unique aspects to my pre-show routines. It also had one gloriously unique piece of house scenery.

First the customary routines, familiar to all backstage folk. Getting into your blacks to promote invisibility. Checking the call sheets to ensure the actors are all in the house. Knocking at each dressing room to check temperature and climate of the company and the leading celebrity. Prop tables set, scenery in place for the top. The time-honored calls – first the half-hour, and then the fifteen. Working with front of house to open the doors, while hearing the muttering of the audiences who were, in this theatre, generally big and happy. Checking in with the crew heads, props, carpenters, and electricians, particularly the flymen and the often-beleaguered wardrobe man and dresser. Checking the sightlines and masking, so the secrets of the backstage could remain so. I always liked to put a hand on the grand drape, red velvet, heavily weighted at the bottom, and look upward to the distant grid, still on the same hemp rope system installed in 1890. Quick look at the prompt script; leave it open to the top. Test the cue lights and headsets. Before the five, work lights out and pre-set up, at which point the dimness and the cavernous backstage could begin to work their magic. Take my place at the calling position, where 100 years of predecessors had also stood, stage right downstage near the flyrail, the center of it all.

And the un-customary, the unique-to-Elitch’s. The auditorium was cooled by a set of overhead fans, making a steady whirring sound on hot summer nights. Woe (I say, woe!) to the stage manager who neglected to turn those off before the curtain went up, and the actors began to speak. Do not spoil those star entrances!

And then, at the five-minute call, a moment particular to this house.

In the farthest downstage position, closest to the audience, Elitch’s had a house curtain from the golden age of American scenic art. Hand-painted by brush and stencil in 1894 by the Charles Thompson Scenic Studio of Los Angeles, rich in color and complex in decoration, the curtain’s central image was an English-style cottage-in-a-garden, with a cartouche that declared, ungrammatically but charmingly “Anne Hathaway’s cottage, a mile away, Shakespeare sought, at close of day.”

Hence, the “Annie.”

At the five-minute call, the stagehands, with care and a touch of ceremony, flew the old curtain up and out of sight, revealing the deep folds of the grand drape, the last thing left between the actors and the audience. When it, too, flew, the house lights went down, the stage was revealed and the play began. Far above that noise and glamor and sound, the glorious Annie, like a huge painting, would hang silently in the dark of the flyloft, always there and always ready.

Research tells a little. In 1890, Elitch’s had been built with 600 seats and a canvas roof “at the end of a winding path through the apple orchard.” There are references that the earliest audiences could stand in the gardens and still hear the play. The original curtain, featuring scenes of the Rocky Mountains and the surrounding gardens would, then, have had exposure to the weather. Was it rained on and ruined? Wind-blown and torn? This is speculation, informed speculation. In any event, after only four years, it was replaced with the Annie.

Why did the theatre’s leadership commission a house curtain with a painting of distant Stratford-upon-Avon? The house at the time was offering six weeks of light opera with four weeks of vaudeville, “suitable family entertainment of the type wholly acceptable to women and children.” Why make the dominant image, the first thing the audience would see, refer to the Bard?

I’ve read that Shakespeare and his works were as well-known in the nineteenth century as today. In his great 1835 book Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville remarked on Shakespeare’s popularity in this country, writing, “There is hardly a pioneer’s hut that does not contain a few odd volumes of Shakespeare. I remember that I read the feudal drama of Henry V for the first time in a log cabin.”

Now there’s an image. “Can this cockpit hold the vasty fields of France?” read by the traveling Frenchman in the log cabin in distant America.

As historian Lawrence Levine has written, Shakespeare was widely performed on professional stages at the same time that he was playfully lampooned in parodies and minstrel shows that depended for their humor on a wide knowledge of his work. Shakespeare, in short, said American Theatre magazine, was America’s most popular playwright, and part of the lore was his older sweetheart Anne Hathaway who grew up in a pretty village near Stratford.

For nineteenth century actors, as in our time, Shakespeare was regarded as a kind of epitome of the art and craft. If you were a Shakespearean, that meant a certain level of skill and depth. So, too, for theatrical companies, and so, too, we can deduce, for growing, ambitious Elitch’s. And possibly for the Colorado audience, for whom statehood was only eighteen years in the past. Playmakers and playgoers alike might have been struck and caught by the imagery of rural England and Shakespeare.

By 1897, the widow Mary Elitch had a resident stock company in Denver, with a full season of plays featuring actors from both coasts. And in the 1900 season, she presented As You Like It as the first play by Shakespeare on the Elitch stage, part of a full season of sixteen productions. Shakespeare had arrived at Elitch’s, and that first audience was greeted by the sight of the Anne Hathaway curtain.

When Mary Elitch and her fellows considered a design for the new curtain for their theatre, they were six years in advance of any actual Shakespeare play on the stage. They likely chose Charles F. Thompson Studio in Los Angeles because the house was a famous painter of theatrical scenery. They were likely shown a display book of curtain images to choose from (one traveling case of samples has survived in a private collection), a central motif that would be hand-painted, surrounded by more standardized elaborate stenciling and painted draperies. They saw the image of Anne Hathaway’s rustic cottage, “This one,” they might have said. “Let’s have this one.” And so it was painted, and rail-shipped to distant Denver, and hung for the 1894 season, where it remained in use, until the theatre’s closing in 1987. The surrounding hard goods were painted to match. The reveal of the new house curtain was likely a notable moment in young Denver’s cultural life. Just a few years later, in Minneapolis, a newspaperman wrote about the importance of a new piece of scenery this way: “The disclosure of the new drop curtain was an event of the evening, and its advent was hailed with acclaim by the large audience present.” So, too, we can speculate, in Denver.

But how did that image get into that display book?

When scenic art historian Wendy Waszut-Barrett looked at a photo of the Annie, she grew thoughtful, and turned to the files of her company, Dry Pigment. “Oh, right,” she said, “I thought so, Peg. There it is.” “What?” I said. The image she found in her files was (astonishing to me) the exact same view of Anne Hathaway’s Cottage.

Wilfrid Williams Ball (1853-1917) was a British Victorian and Edwardian painter of landscapes. In the early 1880’s, near the beginning of his career, he made a series of etchings and paintings on a trip from London to Stratford-on-Avon. Shakespearean tourism was quite a thing in that period, as it is now. His watercolor of Anne Hathaway’s cottage somehow made its way to the display book in Los Angeles, and thence to the house curtain in Denver. (Versions of his image can be found on ebay to this day.)

Emily White of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford, which manages the cottage, supplies a clue. “Anne Hathaway’s Cottage became symbolic of England, and was used by numerous companies to sell their products. That particular view of the cottage was, by far, the most favoured by artists. It is also the view which visitors saw when walking from the center of Stratford upon Avon to the hamlet of Shottery to view the cottage. By the 1880s, it was a standard part of the visitor experience to walk the mile from Stratford, using the same historic path that Shakespeare once likely walked.” And much later, Mr. Ball.

White went on. “This is likely where the reference to ‘Anne Hathaway’s cottage, a mile away, Shakespeare sought, at close of day’ originates. Indeed, visitors could pay to visit the cottage by the 1880s, and were asked to sign their name in the visitor book by a descendant of the Hathaway family, who still lived in the cottage. Some were moved to write little poems and verses alongside their name, so perhaps this was what the artist wrote.” She added – and I could almost feel her smiling through the email — “Pure speculation.”

It is a pleasant reconstruction (see “speculation” above, and repeated use of the word “likely”) to think that Mr. Ball’s work, perhaps on a commercial product of some kind, was seen in Los Angeles, was seized upon by the scenic studio as an attractive theatrical image, and was chosen by the representatives of the grand Denver playhouse for their new curtain. The drop greeted audiences there for nearly 100 years, was treasured by the theatre, and greatly admired by me every night when I walked across the stage before opening the house.

It is less pleasant to recount that in interim years, after the closing, when the playhouse was still standing but before restoration, its roof leaked. The Annie was first damaged, then terribly damaged, then taken down and folded up in a dressing room. The building is still standing, and bravo to that, but when the Annie was last unrolled on the stage floor, only paint flakes and dust were left.

Chris Hadsel of Curtains Without Borders looked at the Annie in dissolution, and said there was nothing left to restore. She has made a study of the remaining painted curtains in grange halls and small theaters in New England. Apparently there are many. At least one other major scenic studio of the day, Twin Cities Scenic Studio of Minneapolis, seems to have also had the Wilfred Ball cottage image in their files. If the design was available through two major studios, it seems possible that someone else might have chosen it. Could another studio have also made an Annie?

This is another pleasant speculation, although one expert said decidedly that the Annie was a one-off, a design painted just one time. No way to know.

I like to think, too, about the upstage side of the Annie curtain, which would have been visible only to actors and theatre workers. The audience-facing side of many curtains featured advertising for local businesses, and the revenue from those ads helped pay for the cost of the curtain. But the Annie was the only curtain I’ve ever heard of with advertising painted on the upstage, the “back” side. Those ads must have been intended for actors in town for a show or series of shows, or traveling through. An Elitch historian transcribed two ads in this way: “J.H. McCracken of ‘Saddle and Light Livery’ at 1413 Broadway offered ‘Horses called for and delivered, riding tonight.’ Haberl Jewelry Co., manufacturing jewelers, offered ‘special prices to the profession.’”

The Annie, with its downstage glamor and upstage ads for a livery stable, is lost now; we are fortunate that the theatre itself has been saved. Old theatres, and new ones, traditionally leave a single light burning on an empty stage, the last thing lit before the doors are locked at night. It’s often just a single bulb on a stand, with a long extension cord leading into the wings. It doesn’t reach into all the dim corners or up high above where the Annie once flew. But it can serve as a gathering place for the spirits and history and energy that fills these old houses, which is why they are traditionally called “ghostlights.” A ghostlight still burns on the old stage at Elitch’s; perhaps a ghostly echo of the Annie hangs in the dark above.

*****

For more Motley on the historic Elitch Theatre, with backstage tales and humor, see Summer Stock Theatre, in the Grand Old Style (02.07.24)

Photo by the author, of a postcard of the Annie. Among the sources: Christopher Kirkland’s history of Elitch’s. Denver’s Historic Elitch Theatre, by Theodore A. Borrillo. American Theatre magazine. Suspended Worlds: Historic Theatre Scenery in New England by Chris Hadsel. The Twin City Scenic Collection, University Art Museum, UMN. Thanks to theatre scholar Dennis Behl. See www.drypigment.net. See www.curtainswithoutborders.org.

See historicelitchtheatre.org. Thanks to Greg Rowley, board president.