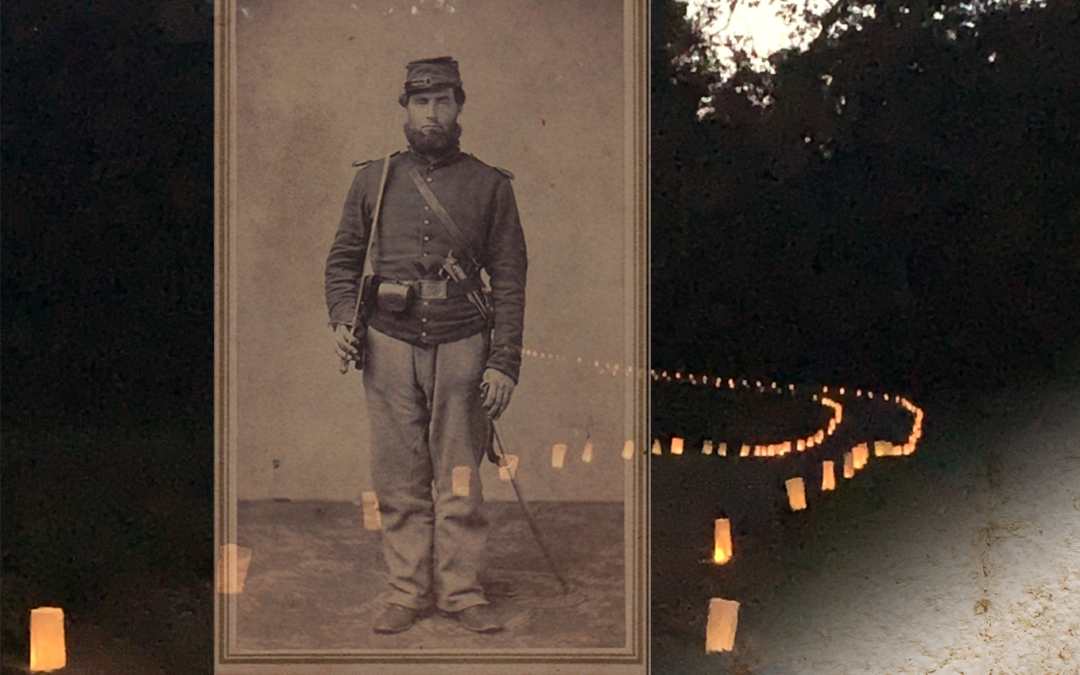

The proximate cause of my Civil War thinking is a carte de visite that emerged some years ago from a cardboard box in my grandparent’s home. The upright young man in Union army uniform is resolute and bewhiskered. Three separate inscriptions are on the back of the old cardboard. Faint pencil reads “Grandpa VW”, which would place the scribe somewhere in my grandmother’s time. One generation later, my aunt’s back-slanting script notes “Great, great, great grandpa Van Wagner to Peg.” And then one I wrote myself some decades later: “George Herbert Van Wagner b. 1838.” I can’t believe I used ink.

I’ve long had an inclination toward and a weakness for Civil War history, a rich period for generalized field research. Looking at “Civil War George” – so called to distinguish him from three succeeding generations of Georges – led way onto way, both back and down through time and history. Reading histories sweeping and specific, examining family artifacts, consulting genealogy sources, led eventually to a research trip to his home territory in upstate New York. His life began to be revealed.

George was a cavalryman in the Third New York Volunteers. The photo was taken in Rochester, shortly after he mustered in in August of 1861; the one I have was probably sent to his mother Catherine or sweetheart Mary Susan, and has survived 162 years in some box or another to come to me. The farm boy must have been a horseman; he was assigned to carry regimental mail from Washington DC to camp and back. From an obituary, “This was constantly on the move and each morning when he left the camp he was told where to find it on his return…he slept alternately in a bed in the city and on the ground in camp.”

According to another soldier, “many times when he arrived in camp it was late and when it was rainy he was exposed and on one of these occasions he arrived late cold wet and there being no fire and having no change of clothing took a severe cold which settled on his lungs.”

In October of 1861, the 3rd New York Cavalry was at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff on the Potomac River, outside present-day Leesburg, Virginia. The battle was ferocious, with George on its fringes, perhaps sleeping on the ground in the rain. Within a month, he was sent to hospital and later discharged with terrible lung problems which would never clear. They called it phthisis then; now we would call it pulmonary tuberculosis, progressive and systemic. He drew health-related pension for the rest of his life.

In 2022, I visited the Ball’s Bluff Battlefield Regional Park for a day of events commemorating the 161st anniversary of the battle. There were interpreters, tours, a Civil War band, cannon, and a skirmish. Re-enactors marched roughly about in period uniform, learned how to stack their arms, camping in the chilly autumn woods in period tents behind a hand made canvas sign that said “Sons of Maryland! To Arms! Our borders are overrun by the Yankee horde. Rise up and defend your sacred rights, your homes, your mothers, wives, and sweethearts…”

My Civil War George served for the Union, but this battle took place in the South. He was a small-town farmer who’d likely had ridden his own horse 13 miles to little Medina, New York to enlist in response to a call from the New York governor for 25,000 volunteers. He was part of “the Yankee horde.”

The woods were in autumn dress and the ground covered in leaves that crunched as the re-enactors marched, sticking largely to the lanes, although their forebears had fought their way through rough terrain and up and down a bluff, and across the Potomac. One soldier in blue, with authentically long hair, practiced his fife alone in a field before being joined by a drummer. It was a day worth thinking about, not least because of the deep commitment and memory of the people attending. It was a solemn matter.

I looked through the woods in the direction of Washington, and thought about George somewhere in transit with his mail pouch, and soldiers from both sides facing murderous fire, to lie where they fell, to await the rough medicine of the day; almost 500 were wounded.

At night, perhaps forty of us returned for a cemetery ceremony. It was late and dark, and the approach was lit only by 259 luminaria, one for each soldier who died at Ball’s Bluff. We sat in rough chairs facing a ceremonial cannon, each of us provided with a sheet of paper with names of the dead. Name, home town, age. I was given part of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry roster, almost all privates, the youngest of them just nineteen.

My list included two brothers, John and William Kidder, ages 25 and 27, from Walker, Massachusetts, outside Boston. With their company, they had splashed across the Potomac in the night toward a camp that turned out to be a row of trees; the Battle of Ball’s Bluff was the result of a mistake, but fighting began anyway, and lives were lost. Perhaps their mother, or sweethearts, also had an image to cherish and save; perhaps their descendants still have them. I’d like to think so.

Each person took their paper and read in turn into the quiet dark. And then each person took a last look around at the dark battlefield, and walked out past the guttering luminaria to their lives, leaving the dead behind.

Poet Theodore O’Hara was a lieutenant colonel in the Twelfth Alabama of the Confederacy. His best-known excerpt:

On Fame’s eternal camping-ground,

Their silent tents are spread.

And Glory guards, with solemn round

The bivouac of the dead.

Photo by the author.