“We pledge to fight ‘blue-sky thinking’

wherever we find it.

Life would be dull if we had to look up

at cloudless monotony day after day.”

(from the manifesto of the Cloud Appreciation Society)

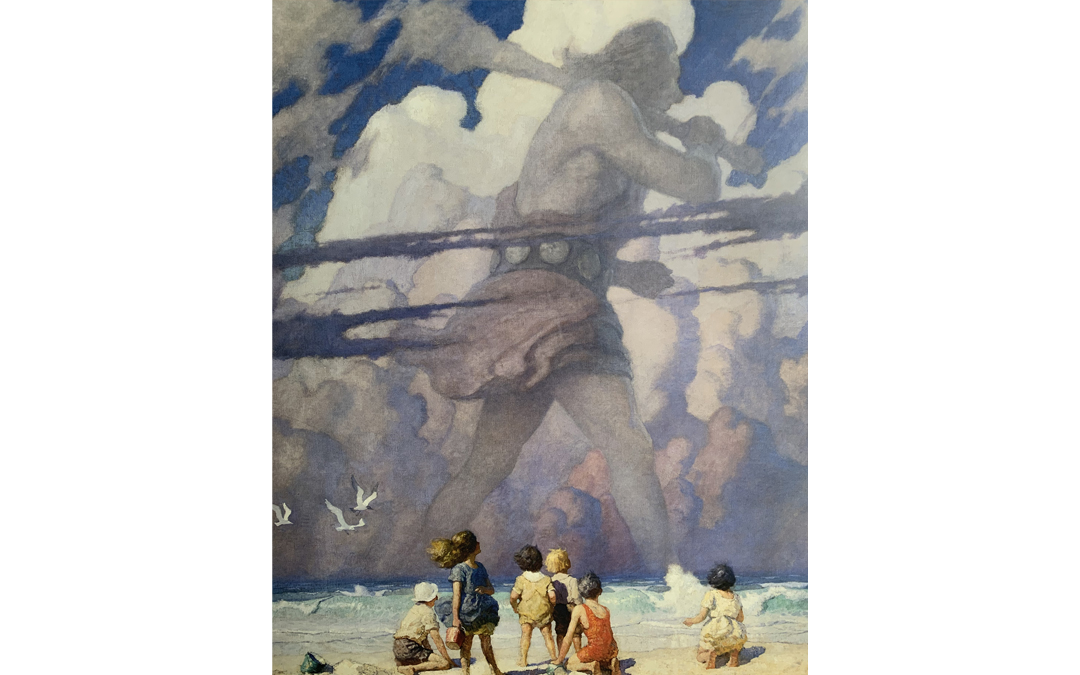

I have been a sky-watcher all my life. Among other treasures on my grandparents’ spine-faded bookshelves, were the Scribner Classics, a series begun in 1904 and featuring many of the best illustrators of the twentieth century. Some twenty-five volumes (Treasure Island, Last of the Mohicans, The Scottish Chiefs, The Boy’s King Arthur) featured the work of N.C. Wyeth, with cover images and interior plates that carried me far away from that little house outside Chicago, onto islands and into the primeval forest and the Scottish highlands. N.C. Wyeth died five years before I was born, but his work shaped the way I look at the sky.

Illustrators and painters are storytellers as much as writers, and one of Wyeth’s greatest atmospheric techniques was his work with clouds. His pirates and frontiersmen, knights and chieftains, were nearly always framed by startling skies and when I settled into the big rocker in my grandparents’ modest home, that luminous imagery leapt from the page, opening a passageway to Stirling Castle or Sherwood Forest. If the early twentieth century prose of these stories now seems complex and even turgid, the stories are evergreen, and the paintings still rich and vital.

Passageway, and escape route. There were considerably fewer towering landscapes, and less drama outside the pages of the books. The plunk plunk plunk of practicing piano, arithmetic with Sister Rosario, and fish sticks on Friday night did not match the soaring visions of my book-fed imagination. I was always looking at the world with the mind’s eye. Perhaps you were, too.

And I saw things in the clouds, as the children do in Wyeth’s The Giant. Just like those little ones with their buckets and shovels, I spent much of my childhood on a beach gazing upward at the changeable mighty skyscape over Lake Michigan. Every moment, the world presented itself in clouds and drama and limitless change. Wyeth painted The Giant, I read, in memoriam for a student lost to tuberculosis. The original, a full five by six feet, has been hanging since 1923 in an East Coast boarding school dining room, where boy and artist met. The figure in the white hat represents the lost student; the others are meant to be Wyeth’s own children. In distant Minnesota sixty years later, I hung a far-smaller copy of that image for my children when they were old enough to start their own lives of sky-gazing, and one hangs now in the shared room of my little granddaughters, who are the right age to find the cloud-shapes and the giant shape equally real. The girls still live in the uneven liminal space between the tangible and the intangible, the probable and the improbable, on the beach in the wind.

Not long ago, I sought a conversation with a plein air landscape painter who has worked for decades to transfer the limitless depths of clouds and sky to the little flat surface of the canvas, changing it to a world into which the viewer can step. Mary Pettis is an expressive realist who says “When I paint, I truly feel the great relations among all things. Every subject becomes a metaphor. I forget to breathe.” Our conversation was rapid, packed, and fascinating. I, too, forgot to breathe.

There is a photo on Pettis’s website which expresses the joy she takes in her art. She is standing on a rocky shore with her working gear at hand, canvas and brushes. On her easel is the waterscape she is painting, water and sky. The foremost wave on the canvas is no longer present in the world; she caught it in its moment and recorded it, so her painting will hold a moment that no longer exists. Mary says that her paintings — I would say this particular photo is a direct demonstration — are like an aperture into the world, and although the rectangle of her canvas captures a kind of lens view, necessarily framed by its edges, her own vision extends beyond the canvas to encompass everything. “I like to feel that every painting gives someone a sense that this world continues all the way around them. The same quality of light is coming out of the sky and landing everywhere, even though we see only its corners.”

It seems to me that this gives her work a kind of mystical extension from the canvas into the world she was regarding with such close attention when she painted it. What was the light? Where was the sun? How were the clouds moving, and what were all the colors needed to hold those clouds on her brush and then to release them onto the canvas? Orange? Blue? Green?

With Pettis’s work, the conscious and unconscious response of the viewer are congruent. Our responses do not stumble over anything. “Each cloud has its personality, but it’s all connected, like walking through a crowd in Times Square. We’re bumping shoulders with other human beings. We look. We pause at the details or where there’s a bright color or an interesting note.”

“It’s like a musical score. It gets quiet and then there’s a little tinkle and then the sky has to be sympathetic to the painting. The sky and the clouds balance the view and help us stay in rhythm and harmony and not discord. When the color of the sky is in perfect sympathy with what’s happening on the land, we feel at peace. We feel it’s right.”

And I’d venture that you might say the same thing about the function of the sky and the clouds in the real world. The feeling of peace, of, as she says, “perfect sympathy” can occur when we’re walking through the landscape, not painting it. A good reason to look up.

Surrounded by her paintings in a gallery, I ask her “Are you drawn to sunsets or sunrises or stormy skies, or calm ones?”

“Yes,” she answers, beaming. “Yes!”

There is, almost certainly, a scholarly dissertation somewhere positing that the human desire to belong to a group is traceable back to our time huddling in caves and evading predators. And almost certainly, some Gen-Z’er is at work on another tome connecting that idea with our contemporary inclinations toward affinity groups and memberships. I am, for example, an eight-year member of the Cloud Appreciation Society and I am hardly alone. My membership number is 40,637.

The Cloud Appreciation Society, based in Britain (of course), publishes a cloud image every day direct to one’s inbox. Members from all over the world send in their photos, tagged by location and with a few words describing the classification of that particular cloud. The effect is a daily tour of the world’s beauties, and a reminder that all people everywhere are standing under the same high sky. Lenticularis over Nerja, Spain. Towering cumulus over the Temple of Zeus, Greece. A turbulent storm system over central Singapore. Nacreous clouds over Elgin, Moray, Scotland. Cirrus over Cogdill Center, US.

And I’ve learned something else from the Cloud Appreciation Society. Sometimes their Cloud-A-Day is from a painting, which reminds us that the sky is infinitely interpret-able and style-able, and exactly the same and wildly different for every observer. David Hockney paints clouds differently than Georgia O’Keefe, who saw in a different way from Jim Denomie, who is entirely unlike Charles Russell. Or Mary Pettis. Or N.C. Wyeth. When I visit an art museum now, say the Minneapolis Institute of Art, with its relative silence, wealth of beauty and rush of images, I sometimes employ a personal sorting mechanism, letting my eye glide through a gallery and catch on all the paintings with clouds. Then I step over and stand in front of them and consider the infinite variety of our world, and the infinite wonder of the artists’ eye.

And then I go outside to find a spot between the trees of south Minneapolis. And then I look up.

*****

Feel free to share.

Additional favorites at MIA, the Minneapolis Institute of Art are Marsden Hartley, Carnelian Country. Julius Holm, Tornado over St. Paul. Edwin Dawes, Channel to the Mills. Recommended book: The Cloudspotter’s Guide, the Science, History, and Culture of Clouds, by Gavin Pretor-Pinney, the founder of the Cloud Appreciation Society.

See cloudappreciationsociety.org and marypettis.org. Photo by the author.