In Chicago this winter, I spent a solitary day at the Art Institute, wandering happily among many things I love. The Impressionists! The Greek and Roman galleries! “Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte”! Arms and armor! The Thorne Rooms! All worthy of many exclamation points.

This visit, I re-sorted my time a little, accessing the collections list and using keyword “Minnesota” to see what turned up. Many wonderful things did – Gordon Parks, a Frank Gehry concept sketch of the Weisman, Jasper Johns, a Warren McKenzie pot.

There are 66 artworks on that list. All but one are in storage; I imagine a long climate-controlled shelf with the 66 owned pieces and a small arrow marked “Minnesota”. Could there be just one available to see? The curator helping me checked my methodology by using another state name as a search term; “New York” turned up 4,135 artworks. I poked him a little. “What”, I said, “is the Institute thinking? So many related to New York and so few related to Minnesota.” He smiled and gave me directions.

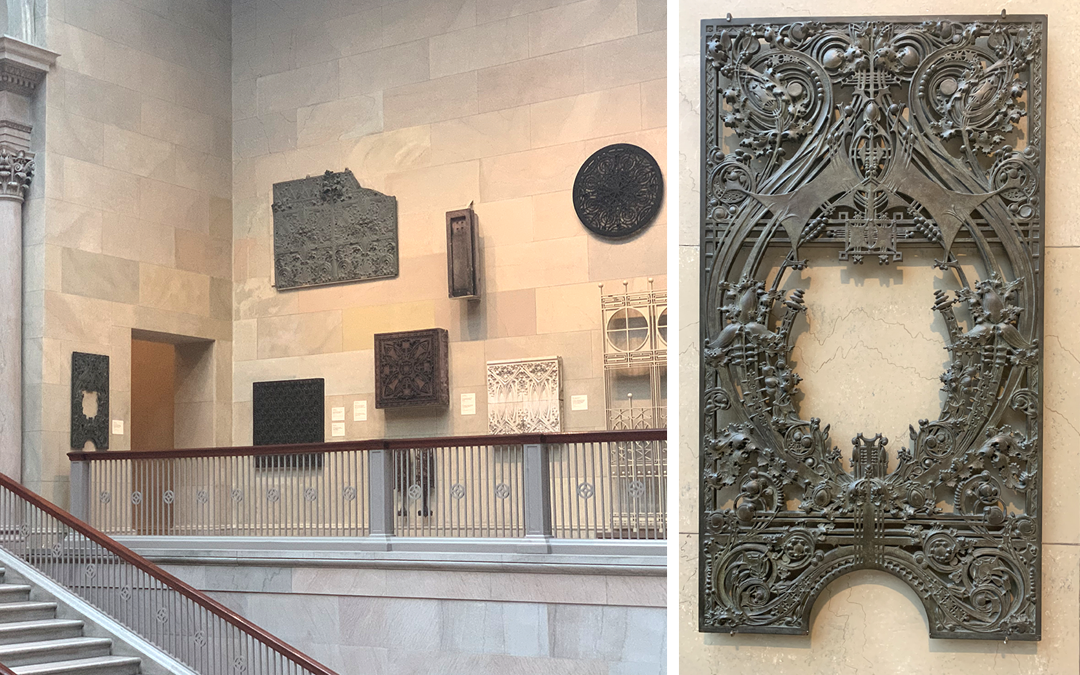

The piece on view is in a grand location in the huge atrium that surrounds and encompasses the Women’s Staircase. Its official name is “Teller’s wicket from the National Farmers Bank, Owatonna, Minnesota, 1906/08”. It, and the bank, are the work of famous architect Louis Sullivan, who strongly influenced the Prairie School, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

A wicket, I learned, is “a service window where a customer conducts transactions with a teller”. Hence the bottom slot, where paper and money could be given or received. And, I suppose, hence the beautiful oval framing which, now, makes it easy to picture a smiling teller, a woman with hair piled on her head, in a white high-necked blouse, starched and crisp. “Hello”, she would say. “How may I help you today?”

In the Owatonna bank, the farmers bank, I think it likely that the teller would have known most of her customers, so let’s make it “Hello, Mr. Nillson. How may I help you today?”

The wicket is made of copper-plated cast iron, curlicued and elaborate and hardly a straight line in it. The curators at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (which, curiously, possesses a 1967 cast of the one which is in Chicago) say it is “overlaid with scrolling curves and organic designs of pods, leaves, and berries. The abstracted, highly detailed natural forms are meant to be seen and appreciated at close range.” So, I’ll bet, was the face of a young smiling woman in the teller cage, framed in that ornate oval.

The Chicago wicket was given by the manufacturer to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1908. Seven others were mounted in the bank, and removed in renovations in 1929 and 1940. None of them has survived; if the prescient manufacturer had not made its gift to Chicago, the ornamentation work of Scottish-born George Grant Elmslie would exist only in dim photographs.

Chicago credits Louis Sullivan as the artist, and the Elmslie name does not appear. MIA credits Elmslie as the designer, noting that Sullivan designed the building. Elmslie was Sullivan’s chief draftsman and ornamental designer, at one time sharing an office with Frank Lloyd Wright. He was part of the team that designed the Purcell-Cutts House in Minneapolis; he maintained partnerships and an office in Minneapolis from 1909 to 1921.

I like to think of these fertile minds, the Prairie School minds, intersecting with each other over their lifetimes in the Midwest, and leaving us with buildings, ornaments, beauty that still strikes the eye with pleasure. Two of them together, or three, collaborating, quarreling, reuniting, a fluid interaction of ideas, the manifestation of which is still available to our Midwestern eyes.

In the later part of his career, Louis Sullivan and his associates, including Elmslie, took commissions for a series of smaller bank and commercial buildings in the Midwest; the Owatonna National Farmers Bank is one of them. Between 1908 and 1920, he designed nine; they are sometimes called Sullivan’s Jewel Boxes. All still stand. Many have remarkable Prairie School details extant, including a massive stained glass arch window in Owatonna. Owatonna is 69 miles from Saint Paul. It would make an excellent road trip. See the wicket in Chicago, or at MIA, beforehand.

Other possible stops on a Prairie School exploration? The Purcell-Cutts House in Minneapolis, the Harold C. Bradley House in Madison, Taliesin, Milwaukee, Mason City, resting your eye on surviving traces of a time when new ideas influenced the built world of the Midwest, making it even more beautiful, and standing ever since.