“Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year…”

Here comes the eighteenth of April again.

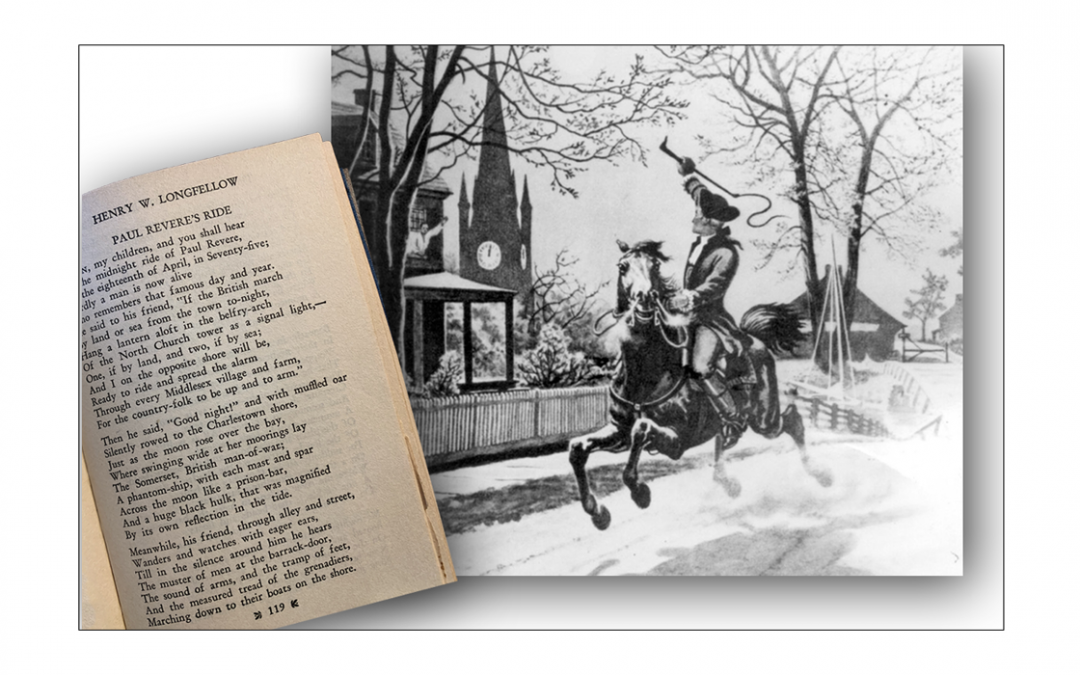

I read that poem periodically for the pleasure of it. The famous ride warning the American rebels that the British were coming took place in 1775, nearly 250 years ago, and “Paul Revere’s Ride” made it legendary 160 years ago, after poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow made an early-April visit to Boston’s Old North Church. True even then that “hardly a man is now alive that remembers…” And yet, that propulsive rhythm, somewhere between infectious and mesmerizing, still rolls, still catches and holds the ear, turning sound into something else. Listening, you can almost see the dark night, the rider poised, the looming battle, the threat of war. Would it come? It did.

The poet was writing in 1860, in the face of another impending war. Would it come? It did again.

Some 110 years after the poem was written, my mother and I were on a road trip. I believe she was at the wheel of the big green and white Chrysler, her absolute favorite until the Lincoln came along. We were passing the highway time trying to remember poems we knew by heart, niggling at each other, calling out lines, having both acquired a taste for rhythmic narrative on her parent’s dusty bookshelves with its representatives from nineteenth century literature. As a girl, she read for escape from her home; decades later I gravitated to those books for escape from mine. “The World’s One Thousand Best Poems”, the 1929 printing, sits on my bookshelf today. It is full of curled and faded scraps of paper, marking poems we loved. Longfellow is in Volume VI.

I remember that day pretty well. The high blue Midwestern sky, cornfields, a road map on the dashboard, snack wrappers on the seat. My mother was free and beautiful then, and she liked to drive fast, and be noticed. She might have been taking me to college; I might have been wearing a lime-green pantsuit, shortly to be discarded for ragged bell bottoms. A twentieth century scene with a chyron of nineteenth century poetry, framed in laughter and an edge of challenge. She did like to shine.

“In Flanders field, the poppies grow

Between the crosses row on row…”

(McCrae)

“The little toy dog is covered with dust

But sturdy and staunch he stands…”

(Field)

“I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills…”

(Wordsworth)

“The gingham dog and the calico cat

Side by side on the table sat…”

(Field, again. She liked Field and so did I.)

“And the highwayman came riding –

Riding – riding

The highwayman came riding, up to the old inn door…”

(Noyes)

And on and on, pausing and teasing, with the ghosts of the poets riding along, not in their rather grim period portraits, but smiling and enjoying our enjoyment. We’d get one and forget one, helping each other. And now, after many more years, this is one of my favorite memories of the time we spent together, speaking an uncommon language that we had in common. Late in her life, when she was abed, I would read those poems to her again, between watching black-and-white films from the forties, with slightly dangerous heroes and dashing beauties in peril and a smart hat. The poems from long before her birth, the movies from her young womanhood, the twenty-first century life passing by in the hallway and in the street, before she departed.

The poem and its romance still hold together for me; it is historically inaccurate, but full of portent. I can see that idealized Revere, booted and cloaked, watching for the signal.

“One, if by land, and two, if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm…

A hurry of hoofs in a village street,

A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,

And beneath, from the pebbles, in passing, a spark

Struck out by a steed flying fearless and fleet;

That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light,

The fate of a nation was riding that night;…”

I think of the sound of the poem, and the note of alarm, and the state of the country I love, and I hope the last stanza is still true for us, for now.

“For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.”